Three hour meeting bundles start at $700.

Start on a new journey today.

Three hour meeting bundles start at $700.

Start on a new journey today.

Sign up for our Muse-letter now!

By Ivan Barnett

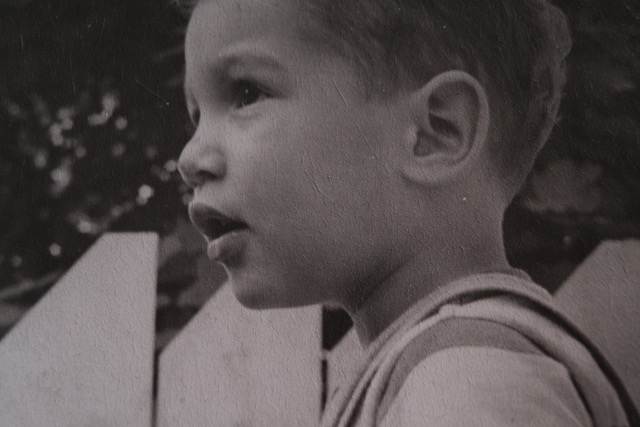

Ivan age 3, “always observing and staying in the moment.” 1950. Image Isa Barnett.

“Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” — Pablo Picasso

When I read Picasso’s words, I don’t hear a lament; I hear a diagnosis. Children arrive with a native creative metabolism, curiosity without apology, experiments without verdicts, and a tolerance for failure that adults spend fortunes trying to recover. Somewhere along the way, that metabolism slows. Rules multiply. Grades and judgement arrive. We begin to narrate our choices to imaginary voices. By the time work reaches a gallery wall, many artists are asking permission from an imaginary judge who doesn’t exist.

I’ve watched this arc for five decades, from my own studio, to the years at Patina Gallery, and now through Serious Play, where I help artists and galleries reconnect to the engine that made the work possible in the first place. If childhood is a kind of creative inheritance, adulthood is the long negotiation of how to keep it.

What changes as we grow up? First, our relationship to risk. Children risk automatically. They draw, paint, tape, stack, then run to the next thing. There’s no register. Adults keep registers. We measure time, price materials, anticipate reviews, pre-write the comments in our heads. Risk becomes expensive. And so we hesitate, polish early, and sometimes never begin.

Second, our relationship to judgment. Children share what they made because making is already the point. Adults share to be validated. In galleries, I see this when artists apologize for what they haven’t resolved yet, as if the conversation could only start once the piece crosses some imaginary finish line. But wonder doesn’t start at the end; it starts at the edge where the maker is still listening.

Third, our relationship to time. Children experience time as a wide field. Adults live in corridors, emails, deadlines, openings, etc. Time narrows. We compress process into productivity and confuse activity with progress. The work becomes competent yet strangely without soul.

So the question is not “How do we become children again?” The question is “How do we re-design mature practices, studio and gallery alike, so that childlike qualities can survive?”

Here’s what I’ve learned.

Children ask obvious questions because they haven’t yet been taught to be embarrassed by them. Adult artists often hide theirs. In my creative coaching, I begin by naming the live question that sits under a body of work: What if absence carries weight? How quiet can color be and still read as structure? What happens when line behaves like gravity? Once the question is honest, every choice becomes clearer. Scale, palette, materials, even titling—all of it either serves the question or it doesn’t. And when a collector asks what they’re looking at, you’re not reciting a résumé, you’re inviting them into a conversation.

Galleries can help by curating questions, not just categories. Pair works that ask differently. Write text that poses the inquiry plainly. Your audience will lean in because they recognize inquiry.

Children play to learn; adults learn to avoid risk and be perfect. In my own practice, I fight that drift with what I call serious play, structured experiments that are small enough to fail and fast enough to repeat. Make three studies before the one you’ll show. Build rules that provoke rather than constrain: one material, two planes, three decisions. Document what turns. If you’re a gallery, invite your artists to show a study alongside the “finished” piece. It’s remarkable how often the study carries the breath the final work has missed.

Play is not permission to be sloppy. It’s permission to learn in public, where art actually lives.

Ivan playing in the back yard in Germantown “GO PLAY.” Photo- Isa Barnett.

Children stop when they’re bored or called to dinner. Adults often don’t know when to stop. We sand until life disappears. Years ago I began photographing works at three stages—a habit I still teach. Something almost mystical happens when you line up those images: somewhere between second and third a piece “breathed,” then got overruled by competence. Learn to stop where it breathes. That decision is not mystical; it’s practiced.

For gallerists, “stopping” means resisting the compulsion to over-explain. Let the first impression or look do its work. A room with a single clear hook leaves room for discovery, the most childlike experience there is.

Parents hang children’s art not because it’s technically extraordinary but because it is unmistakably alive, awkward, brave, honest. Much of what unsettles people about AI images is the opposite: they can feel frictionless, without the residue of decision we read as human. In my own language, I call the residue intrinsic surface patina, the trace that time was here.

As we mature, we’re trained to remove the very signs that prove the work is alive. I’m not arguing for sloppy; I’m arguing for evidence. Let a tool mark remain. Let a seam show. Let a decision be legible. Viewers aren’t looking for flaw; they’re looking for presence. Children give presence freely. Adults must choose it.

The gallery as a school for seeing

A great gallery is a classroom without a chalkboard. It doesn’t merely sell; it shapes how people pay attention. In childhood, we’re taught how to see by adults who point, “Look at that shadow,” and then wait while we discover it. In the gallery, wall order is that pointing. Lighting is that pause. A text panel is that one sentence that tells a viewer where to stand so meaning has a chance.

When I staged exhibitions at Patina, we tested for what I called the first hook, the one thing you see from the threshold that invites you into the room. Then we built the second hook deeper inside. People don’t need to be taught what to think; they need to be invited to look longer than the news cycle. Do that, and you haven’t just sold a work; you’ve renewed a capacity the world keeps trying to shorten.

“Sitting for Leon in his studio.” Philadelphia, PA. Painting by Leon Karp of Ivan

Children are blunt. Adults are guarded. Somewhere between, we overshare online and undershare in person. In the studio and the gallery, the right amount of story is the amount that frees attention, not the amount that cages it. I’ve counseled artists who carry heavy personal material: share only what preserves dignity for you and agency for the viewer. You are not obligated to turn your life into content. You are asked to give enough context that the work can be understood enough.

Galleries, too, can measure their words. Avoid the fashion of art-speak that makes the work feel like homework. Plain language and feelings are not a downgrade; it’s a door.

Children make art in public places, at kitchen tables, in schoolrooms, on sidewalks. Adult artists often make art in solitude. Some of that solitude is holy; some of it is harmful. What I try to create now with Salon 1033 is a space where the child and the adult both have a place: candid stories from makers, a little risk in what’s shared, and a lot of listening. It’s remarkable how quickly a room deepens when someone admits the thing they’re actually working on.

If you operate or lead a gallery, host a small conversation before the opening, ten people, one question, one hour. You’ll feel the room change on opening night because the ground has been prepared. If you’re an artist, invite two peers to your studio and ask them not what’s “good,” but where the work breathes. Community at that scale is not networking; it’s oxygen.

Isa and Ivan “being curious always” my hero. Painting in oil by Leon Karp.

I don’t romanticize childhood; it is also a time of clumsy choices and unedited excess. Adulthood gives us tools children lack: patience, craft, discernment, the capacity to sustain attention across months or years. When those adult strengths hold hands with childlike qualities, the work acquires a strange and beautiful authority. It’s no longer “about” freedom; it is free, within chosen limits. It doesn’t perform courage; it has done something hard and left the traces.

My mission now, whether I’m in the studio or sitting with an artist or gallerist through Serious Play, is to help restore that handshake: wonder with discipline, risk with care, play with structure. The child in us starts the piece; the adult finishes it, if the adult remembers why the child began.

If you’ve been feeling far from that child, consider one small move that would have made your younger self grin: a study finished in a single sitting; a wall re-hung to make room for one breath; a text re-written so a stranger can enter. Small moves compound. They always have.

I’ll end with a line I’ve carried for years, another of Picasso’s, because the man understood time: “It takes a long time to become young.”

May your work keep moving in that direction.

If you’re ready to reconnect wonder with discipline—without losing the soul of your work—Serious Play can help. I work with artists and galleries to restore cadence in the studio, clarity in their space, and stories that land. Let’s begin with one conversation and one small, measurable win. Email [email protected].

© 2025