Three hour meeting bundles start at $700.

Start on a new journey today.

Three hour meeting bundles start at $700.

Start on a new journey today.

Sign up for our Muse-letter now!

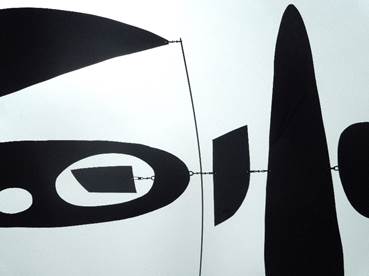

This happens in most studio practices more times than not. Every conversation between artist and mentor, gallerist and collector, a question that hovers silently over the table or sometimes echoes in the middle of the night when you stare at a work: “How do I know when a work of art is finished? How do I know when to stop?” That wise old saying “sleep on it” can often be the perfect solution. Taking a look at the work when you are fresher can be one of the best solutions. Yet, at the heart of the matter, I have found that “the knowing” comes from the years of “going too far,” because you think the work or exhibition will be better or stronger with “more.” That can be the case at times.

However, there’s nothing better than going too far too many times to remind us. Following one’s instincts always is an added skill to have. Then there’s the shared knowing internal knowledge that “a work of art is complete.” Lastly, under certain circumstances, a trusted creative colleagues with similar skills and experiences can be that one collaborator who can say “yes or no” or a “here is what I think.” It is a common practice among creatives to have a trusted, talented artist take a fresh look. In the salons and studios of Paris and other cities decades ago, it was quite common for creatives of all types to share opinions.

For over my five decades as a working artist, nearly three as co-founder and creative director of Patina Gallery, and now, through Serious Play, I hear it from clients across disciplines and backgrounds. Painters. Jewelers. Sculptors. Writers. Gallerists prepare their next show or exhibition. Directors try to make programming sing and be heard, not unlike those salon days. That one outside objective review can make a work or project go from good to great. Yet oftentimes, when we are so close to our creations, we can lose clarity.

Let me say this clearly: completion is not perfection. The search for perfection is often elusive. The real signal of completion is that final moment when the creative can say with ease that “I wouldn’t move or change one thing.” The piece no longer tugs at your sleeve—it offers us a quiet “yes.”

When I work with artists through Serious Play, one of the most liberating things we do is learn how to recognize that shift. We move from making to listening to a work of art. We learn to stop not a minute too late. In my own case, when working on a new series of sculpture and pushing my own limits well beyond my creative and technical comfort zone, I have found the joy of saying “why not” go there or “don’t” go there. And here is where the serious play unfolds and where time seems to slow down. All that is left is you and your painting, the painting that the world has yet to see. I liken this to “giving birth” and a beautiful new child ushers into the world of art to be enjoyed and live in a new space.

Many artists and gallerists exist in a state I call “almost done, not yet done.” They keep sanding, refining, adjusting. Not because the work requires it, but because the thought of stopping feels unbearable for a creative. Maybe it still doesn’t feel safe to be seen. Maybe they don’t yet trust the voice of the piece. Or maybe they’re waiting for someone else to declare it finished.

The problem with “almost done, not yet done” is that it slowly dulls your creative instincts. It robs you of the moment when the work could begin its life in the world. Because yes, a work of art has a life—but not if you do not let it go.

I have spent my entire career living in both the studio world and the gallery world. I am truly able to say with confidence. Together, you and I can help you finesse and nuance being in that stuck gray zone. It is only the geniuses who need no outside guidance. They are the rarest of the rare. The rest of us try to be very good at what we do. If we make the right moves we can go from good to great. It is in the great that “we are rewarded both economically and creatively.” We can go from unknown to known.

I curated some of our most celebrated exhibitions at Patina Gallery—Porsche Portraits, Signs of Life, Abstraction, or Season of Blue. I often worked with artists who edited up to the last minute. While some refinement is natural, I learned to ask simple questions. “Is the work still asking for more? Are you ready to share it with the world?”

A work of art tells you when it’s ready. It may whisper. It may sigh. If you’re present enough and confident enough say “yes, it’s time.” Producing opera collaborations with the famed Santa Fe Opera was always the hardest and most complex.

In any creative venture, knowing when something is neither science or absolute is a must. It’s a practice. And it’s one I return to myself again and again. This happens with my studio, my photography, and the meetings I lead at Serious Play.

If you’re unsure whether the work is done, ask yourself:

Completion is not about exhaustion at Serious Play. It’s about presence. It’s when you stop working on the piece and start being with it. And in that stillness, you recognize that it no longer needs you to shape it. You need to release it.

I often ask my clients to read the book by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. The book talks about the amazing moment or moments. These are moments when we are one with our art or even one with your gallery. Once you experience this, you will rejoice when it comes around again. With the proper experience, you can even develop your own tools to return to that magical place.

Lastly, here’s the truth many artists avoid: The work is never truly complete until it meets the world.

Your sculpture doesn’t breathe fully until someone decides to add it to their collection. Your poem isn’t alive until it’s heard. Your exhibition doesn’t sing until someone stands before it, open to wonder. There’s a famous story about Michelangelo and the Sistine chapel ceiling, in 1508. The Vatican had commissioned a great artist to paint the Book of Genesis creation story in the chapel. One day, Pope Julius II came to Michelangelo and asked when he would be finished. He was already some years late. The artist said, “I will be finished when I am finished.”

We do not hold the entire process alone. And we do not hoard the moment of completion. Releasing the work allows it to do what it was made to do: connect, reflect, provoke, nourish.

At Serious Play, how do you know when it’s done? When the work stops asking. When you feel the breath shift. When you can finally—gently, honestly—say: “This is whole.” And then, you give it life.

© All Rights Reserved